Antananarivo

July 31st 1865

My

dear Sir,

So begins the letter composed by Margaret Milne to officials of the London Missionary Society, after a journey of almost five months. A native of New Pitsligo, she was just twenty-three years old when she left Britain in February 1865. For the final leg of the voyage she was accompanied by another missionary from the neighbouring Aberdeenshire parish of New Deer. Margaret Ironside had been married barely two years when her husband Alexander Irvine died en route to a posting in the Loyalty Islands and a rendezvous was arranged in Mauritius for the two Margarets, who continued to Madagascar together. Having grown up within a few miles of each other, they were already well acquainted.

Female company must have been very welcome to the young male missionaries who had already spent three years in Antananarivo. By the end of November, the Society's printer John Parrett was writing home to report:

My dear Sir,

I have much

pleasure in writing to you by this mail, and informing you that I was married

to Miss M. Milne on the 1st of this month.

In fact two weddings were conducted on that day at the British Consulate in Tamatave, since romance had blossomed between Margaret Irvine (née Ironside) and the Rev. Joseph Pearse, who had also been widowed. In the course of time the British community was considerably augmented by the arrival of young Parretts and Pearses.

Having set up a printing press and taken on native apprentices, John Parrett was kept busy supporting the work of his missionary colleagues. However, his correspondence to the Society's officers in London illustrates the problems which arose as a result of unreliable communications and interruptions in the supply of paper. The activities of French missionaries also caused frustration, as revealed in his letter of December 1879:

The Jesuits have flooded the country with Popish

prints, and we can hardly enter a native house (in the country especially)

without seeing pictures of the Virgin, Saints &c on the walls. The missionaries generally are anxious to

check the spread of these pernicious and objectionable prints...

Missionary children received their early education in local schools but as they grew up, arrangements were made for them to attend boarding schools in the UK, whole families returning together on furlough. In her memoirs written in 1949, Elizabeth Parrett describes the first stage of the ten day journey from Antananarivo to Tamatave undertaken in 1873 by the Parrett and Pearse families, with four and five children respectively:

We all went in palanquins carried on men's shoulders. At night we stopped at a native village, commandeered a good hut (...), put up the camp beds and mosquito curtains and, after a meal of rice and chicken, slept soundly till early morning. (...) It was quite a cavalcade as each palanquin had 6 or 8 bearers, 4 at a time with 2 or 4 to relieve at short intervals. Then there were the cooking utensils, bedding, food, clothes and luggage.

The prolonged stay in Britain provided the children with an ideal opportunity to get to know their grandparents and other relatives and to adapt to the British climate. A winter visit to Aberdeenshire left a lasting impression on eight year old Elizabeth Parrett:

Going home for Christmas, there was a heavy fall of snow and as the railroad stopped at Strichen, four miles from New Pitsligo, we had to go the remainder of the journey in a gig. We got into a drift and were half frozen when we reached my grandmother's. I can remember now, sitting on her lap in front of a blazing fire, while she took off my socks and chafed my feet.

When the period of furlough came to an end in 1875, both couples returned to Madagascar to resume their duties, leaving their children behind in the UK to pursue their education. The 1881 UK census (RG11, Piece 0730, Folio 83, Page 15) shows Edward Parrett at the age of thirteen as a boarder at the school for sons of missionaries at Blackheath in Kent, where Alexander Pearse aged twelve and his ten year old brother James were also pupils. Meanwhile the Parrett girls, Elizabeth aged fourteen and Maggie aged eleven, were attending Marsh Street Mission School in Walthamstow, Essex (RG11, Piece 1730, Folio 83, Page 54). They had familiar company, since the Pearce girls (Annie aged fourteen, Margaret, thirteen, and nine year old Rosa) were also scholars in the same establishment. Charles Parrett, who was just eight years of age, was staying many hundreds of miles away with his Milne grandparents in New Pitsligo (RD 227B, ED 2, Page 26).

Following another period of furlough for John and Margaret Parrett, they returned to Madagascar in 1888 with their daughters, while their sons continued their schooling in the UK. By this time John had resigned from his missionary work and had accepted a position in the service of the Malgasy government. Teaching a group of local schoolchildren occupied some of Elizabeth's time, but the family had sufficient leisure to enjoy a varied social life. An interesting account of the annual Fandroana festival is given in Elizabeth's memoirs:

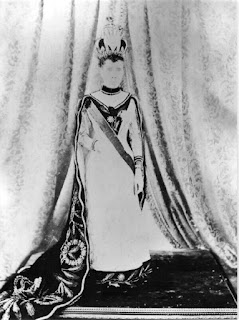

In the north-east corner of the big palace a corner was screened off by scarlet curtains and here water was heated for the Queen's bath (...). Then she retired behind the curtains and had her bath. She emerged resplendent in a crimson velvet dress with much gold embroidery and with a crown on her head - the ceremonial one with the seven "fingers" in front. The Prime Minister carried a pannikan of the bath water and the Queen dipped her fingers in it and sprinkled all those she passed on her way to the great door. There she sprinkled the soldiers and the cannons were fired and everyone lit a small bonfire in their yards and on the hillsides.

This way of life came to an abrupt end in 1895 with the French occupation of Madagascar and the exile of Queen Ranavolona III . The Parrett family, acknowledging that they had no further role in the country's government, sought a new future elsewhere and eventually settled in Tasmania, where John and Margaret ended their days. Despite increasing difficulties and dangers, Joseph and Margaret Pearse remained working alongside other LMS missionaries in Madagascar until 1904 and spent their final years in rural England.

No comments:

Post a Comment